Michele Oka Doner

by Bruce Weber

“Art, for me, comes out of life. It is the peak of life.”

Bruce Weber fell for artist Michele Oka Doner before he even knew who she was. As a frequent traveler through Miami International Airport, the noted fashion photographer long admired the terrazzo walkway Oka Doner had installed in one of the airport’s terminals, A Walk on the Beach(1995–1999), which was inset with cast bronze and mother of pearl. On the occasion of her expansive survey of works at the Perez Art Museum, How I Caught a Swallow in Mid Air, Oka Doner and Weber chatted on the phone about womanhood, the artist’s uniform, and the natural world.

Bruce WeberYour relationship with nature is a total love affair, and it’s one of the things I love about you—you touchthe things you make. When I first went with you to do some photographs, we went to your favorite tree, in Miami. What kind of tree is it?

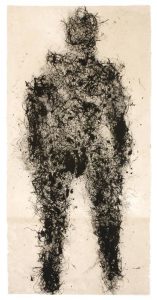

Michele Oka DonerIt’s actually a big banyan, usually seen in places like India, out in the open landscape, never in an urban situation. This tree was left alone, trimmed a little bit by Hurricane Andrew in 1992, but it came back. I love it for many reasons. One is they say Buddha received his enlightenment under a banyan, so it has a holy aspect to it in several cultures. I love it also because the roots come down from the branches and nourish themselves in the humid air. I climbed that tree as a child. We made swings from tying roots together. Recently, I inked the roots and made a print called Birth of Adam. I think this tree represents all the life cycles, the sense of timelessness I kept finding wandering around Miami Beach. I still do, as you know. I wander around and it fills my stomach.

BWWell, there’s a wonderful book called Raintree County—it’s an old southern book by Ross Lockridge, Jr.—and it’s about a mystical tree in the middle of somewhere, where people walk through the forest to find it. And once they do, a lot of really special things happen and a lot of the mysteries of their lives are solved. Do trees do that for you?

MODTrees are like us. They have bark for skin, they need water, they live and breathe; there’s always been magic around trees. My favorite song is the English song “The Ash Grove.” I have a recording of Benjamin Britten accompanying Peter Pears singing. It’s just a gem. So I sing trees, I print from them, I look at them, I see them as family. My favorite, the one I took you to visit, is a real matriarch. By the way, it’s been locked up. They have a new fence around it and you can’t go in. It’s so huge, like architecture, and young people from the high school were going in and getting high. So I had to write the mayor of Miami Beach and request the key. They sent me back a letter saying that whenever I wanted to go, to let them know and they would make it available. And I wrote them back: “No, that’s not good enough, I want my own key. I want to go when I feel like going.” (laughter) So, I’m now in negotiation. I said to them, “This has been my tree for 65 years and I need access.” You know, it’s like locking up my family.

BWDo you know what you said to me when we first met?

MODNo.

BWYou said, “Bruce, I would like you to do a nude of me at the ocean.”

Birth of Adam, 2007, relief print from organic material, 96 x 48 Inches.

MODI did?

BWYes, you did!

MODOh, I think a portrait of me covered with seaweed, that’s what I said.

BWYeah, but you made a pause. You didn’t say that at first, and and I was kind of surprised because I thought, “Oh yeah, I’d love to do a nude of you.” But to take a nude of you where you cover yourself with seaweed? I couldn’t imagine why you’d want to do that. Now that I’ve looked at your work and know what you do and how you are as a person, I totally understand. It would be sort of like if you had that dress on that Marilyn wore to the inauguration of President Kennedy—I think Jean Louis made it for her. It was like a total see-through dress. And I thought, that’s so Michele to choose seaweed as her see-through dress.

I want to talk to you about the uniform of an artist. When I was with Georgia O’Keefe out in Mexico years ago—she was about 92, and she was almost totally blind—she was still wearing her Alexander Calder pin and she always wore black. That was her uniform for, I don’t know, maybe 50 years. Now I’ve always seen you dress the way you do, and it’s like your uniform; it’s what you go to work in, something simple like a black top or a white dress. It’s not so important, the fact that you’re wearing something beautiful, but that’s your uniform and I like that. I really can’t imagine you going out in the world or working in your studio in bright pink.

MODWell, it’s probably true. I like natural palettes—let’s say we’re down at the sea shore, and so it’s got a lot of tannin and iron, and it’s very rich but muted. And it’s the same with walking through a forest. It’s a variation on a theme. The bright colors are very jarring. I wasn’t raised, let’s say, in Brazil in a tropical garden, you know? It’s a different palette, it’s not mine. And the other thing is that clothes are a frame. They’re not anything more than that for me; they’re not the center, they’re not the thing. They’re just a frame.

BW It’s interesting you say that, because when I say to you, “Oh you really look wonderful tonight, or I like your jacket, or I like the jewelry you’re wearing that you’ve made,” it’s almost so much a part of you. Like you might see a carpenter wearing his work belt or his Carhartt Jacket; it’s his uniform.

MODThat’s right.

BWAnd that’s why I love that picture of you that you have in your studio—it’s probably in some book somewhere now—where you’re in your uniform, in your white dress, with a hard hat on.

MODOh! You did point that out. I’m actually at the Miami airport right now, by the people mover they’re installing through my terrazzo floor work, A Walk on the Beach, which was made with my contractor Mario Piombo, a noble guy from Chicago, via Genoa. He always wore the same thing: a khaki, well-pressed shirt—he had it on in that photo—and matching pants. It was khaki toward green, actually.

BWYou know, as a woman, a mother, a grandmother, a wife, I think that the men in your life—your sons, your husband—have played a really big part in your work. It almost has its own gender to it. I have to say that it reminds me a little bit of Willa Cather, who was a great woman. She’s my favorite writer. She wrote a book called My Ántonia, and it shows the strength of a woman who could literally go out and build a house. You seem to be that kind of person. Your work is a bit feminine on one hand and extraordinarily masculine on the other.

MOD I think that the biggest discovery of our time is the word spectrum. We know now that mental health is a spectrum, race is a spectrum, and gender too. So we all have estrogen and testosterone in different stages of our life. It ebbs and flows. Even I wonder what we have to push off against, which you brought up at the beginning of this train of thought. Yes, I’ve lived with men. I have a husband and two sons. I took on the role of the feminine, and I’ve always loved being a woman. I never understood the Freudian notion of penis envy. What? You’ve got to be kidding. And then I had to teach my granddaughter when she didn’t really understand what breasts were—she called them boobs, in fact—and that women loved their boobs, and it was great to be a woman.

BWThat’s what makes A Walk On the Beachso incredible. Way before I knew you I was walking down it, and I thought, “This is the sexiest floor I’ve ever seen. This is the kind of floor you fantasize making love to somebody on at the bottom of the ocean.” And I was surprised to find out that a woman had made it. And yet it makes total sense in a way, the openness of it. It’s weird when we talk about male and female. I had a theatre teacher at Denison University and he said, “Look, it’s not so important if one day you’re in love with a girl and the next day with a guy, and then the next day a horse.” He said it’s just important that you’re in love with something, or somebody.

MODAbsolutely correct. Shakespeare says, “Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediment then… love is not love that alters when it alteration finds.”

BWWell, you know what they call that in Montana?

MODWhat?

BWA tree hugger.

MODA tree hugger? Yes that’s true.

BWAt first, I didn’t understand it, then when I met you I thought I’d want to be a tree hugger too. We share a love for old books, books all torn apart, and things that we find that mean something only to us; that’s something that we share. And yet, you made a book with Micky Wolfson about growing up in Miami, Miami Beach: Blueprint of an Eden. You personalized it so much that it became so special and will, for me, exist as the best book ever done on Miami Beach. What was it like for you working on it?

MODOh, it was a wonderful period. Twelve years it took, because neither of us stopped to do it full time. So every time Micky and I got together we would pick up where we left off and continue to evolve it, and it ripened. That’s why I think it’s lush. We sold out two printings and the book became a textbook—it still may be—at George Washington University in a course called Human Geography. Scholars are looking at the world now through the lens of how people live, not through maps. So geography as we learned it as kids is over.

BWWhen you speak to an artist and they talk about their work, it’s so hard, in a way, to understand what they’re really saying. Sometimes I like to just walk around a museum and look at the works, and then come back and read about it later. I was at a Matisse show and almost didn’t want to know that he did a lot of his paintings from bed, and that he made his collages there. I wanted to look at them for only what they stood for out in the world. Don’t you think that with some of your work it’s two-fold? That you can look at something you made, like a beautiful pin—like a twig, beautiful—and think it looks unreal, though it is real in a strange way? For me it’s a real twig. And yet it really shows our friendship and our relationship. Don’t you think that when you see artwork sometimes it’s good just to see it and not hear anything first, andthenmaybe find out what the artist went through to do that?

MODI agree. I think it’s instinct first, and I think I’m material before theory. I think a lot of the work that has dominated the past 50 years has been conceptual, has had irony or theory. You have to be initiated into the language, and thatyou get from all the magazines. That’s been less interesting to me than work that’s done because it has to be done. The urge to communicate, the urge to express feelings that we know go back at least forty thousand years.

BWI was thinking about all your artwork, and I know it’s in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Louvre… and so many more. But if you were commissioned today to do something for a prison, what would you make?

MODA prison?

BWYes.

MODThat’s sointeresting. Maybe the basin in the prison, where you wash in the morning, you ritualize, you wash yourself at night—it’s life-giving water. Maybe I would make a basin.

BWThat’s what I thought you would say—something like that: the idea of renewal, of growing again, almost like the tree that you showed me, that you loved. It reminded me of my class with Lisette Model. She taught Diane Arbus and was this really great photographer. We were photographing trees, and she said to a young girl, “This tree gives me nothing, and yet it gives you so much.” And the girl said, “I want to see a tree when it’s growing, I want to see a tree when it’s old, I want to see it in a storm, I want to be able to look at that tree and have it mean something very personal to me.” I really feel that’s the thing that separates your work from others: that you’re not afraid to be personal. Sometimes you seem like a tough cookie of a lady, and then other times you seem really frail. But in talking to you I kind of didn’t want to talk about all these normal things that interviews always bring up. I wanted to talk about you in life and in living, because that’s your school, am I correct?

MODThat’s correct, and the—how do I say—fragmented life that is taking place around us is really the pain of the second half of the 20th century. The disassociation from the earth that came with the industrial revolution, and then—there are so many things—we are living at the end of an era, you know? And then Freud opened the door on consciousness. It’s really an extraordinary time we were born in, because it was the beginning of the disillusionment with machines and what they can do for us. And the fracturing, the labeling, all of that is coming back to our discussion on the spectrum. Art, for me, comes out of life. It is the peak of life in a sense, it is the I-Thou dialogue. But you have to first have life, you have to have something to build on, you need a structure to build so you can climb and reach whatever it is you think you’re aspiring to. So you can’t nothave a life. It’s a myth that you can just look at something and say, “Oh I can do one of those,” and think it’s that simple. You can do a one-off, a one-liner, but you certainly can’t sustain that without building a life.

Bruce Weber is an American fashion photographer and filmmaker. He is most widely known for his ad campaigns for Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Pirelli, Abercrombie & Fitch, Revlon, and Gianni Versace, as well as his work for Vogue, GQ, Vanity Fair, Elle, Life, Interview, and Rolling Stone magazines.